At Sea With Sentry

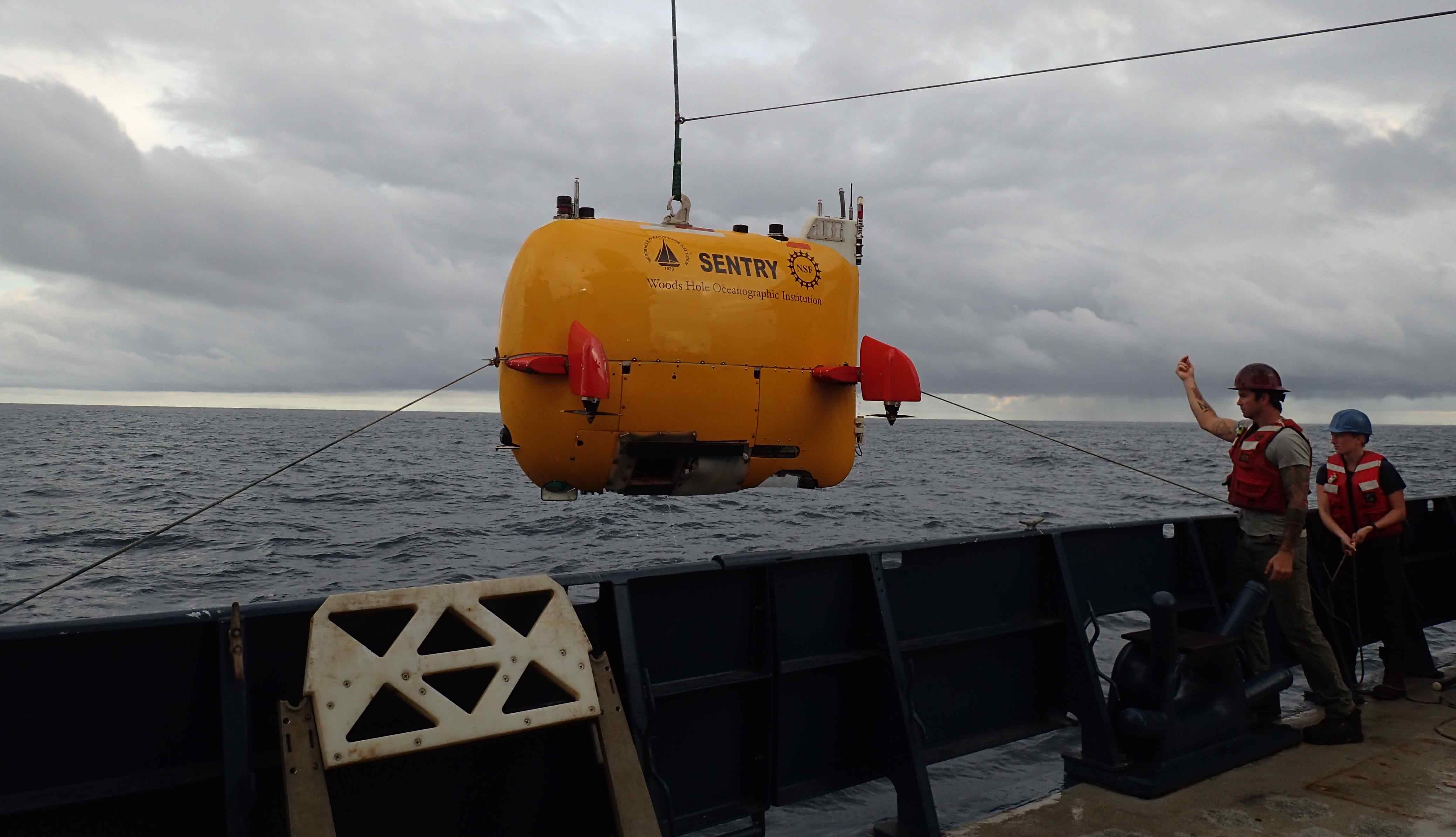

Sentry being brought back on board the Atlantis after a dive

I'm a software engineer in the Deep Submergence Lab at WHOI, and I'm currently at sea with Sentry, a robot whose primary mission is to map the ocean floor. So, what do I do when at sea? And why are they sending software engineers out for operations?1

At sea, my job usually includes:

- Prepping the vehicle for launch (we have an extensive checklist, built up out of years of mistakes)

- Standing watch while the robot is in the water. Depending on the cruise and dive cadence, this will be a 2-5 hour shift daily.

- Processing the data for the scientists after the robot is recovered

- Debugging and fixing anything that goes wrong.

- Using time when sentry is on the deck and during ascents to test new capabilities (we do a lot in simulation, but don’t have a full hardware testbed)

First -- what is Sentry, and what does it do?

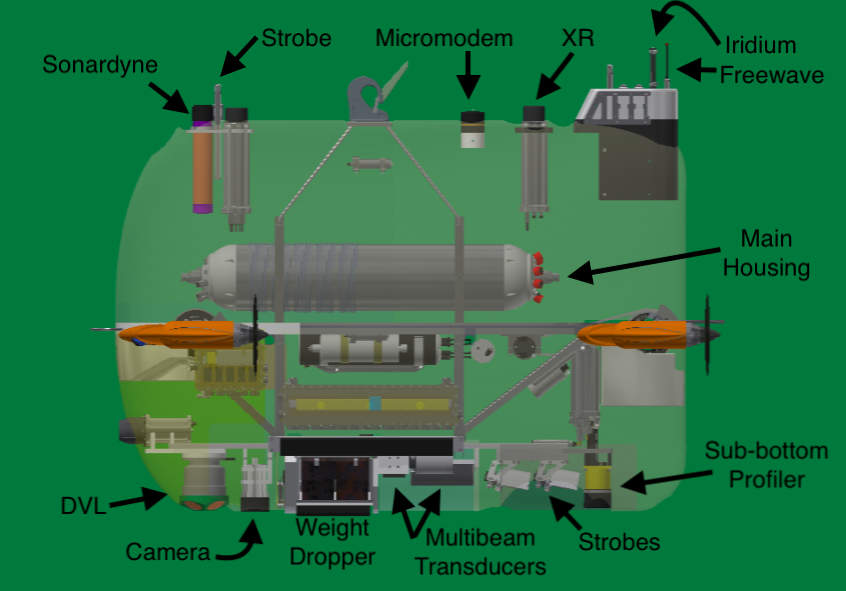

Rendering of Sentry without the skins or syntactic foam, with components mentioned in this post labeled. The Battery Housing has also been omitted for clarity. Thanks to Manyu Belani for the base image.

The original motivation for developing Sentry and adding it to the National Deep Submergence Facility was to create multibeam maps of the sea floor at night for Alvin (a manned submersible) to use the following day during its dive. Of course, once you have a robot with the basic capability to follow a given path, scientists will come up with plenty of other uses for it. So, in addition to multibeam grids, we do a lot of photo surveys, which require swimming ~5 meters above the ocean floor, sometimes in pretty rough terrain.

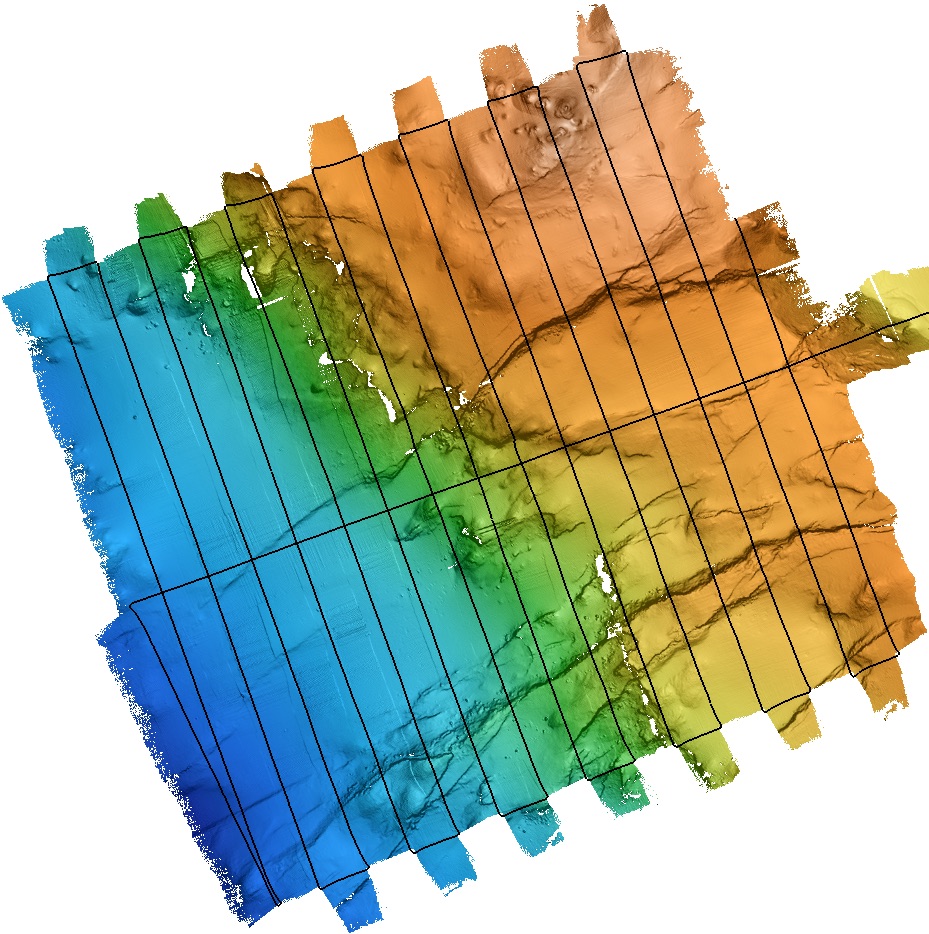

Multibeam data collected on dive sentry505 on the 2018-cordes cruise.2 This screencap was taken during post-processing using mbsystem. Black lines show the path Sentry swam, and the resulting topography is hillshaded. You can see some minor alignment errors where the multibeam swaths overlap that are corrected with further processing.

Plenty of robots can handle smooth terrain -- Sentry’s real strength is in steeper / rougher terrain where its actuated fins allow it to maintain control while slowing down and climbing to a much greater extent than a torpedo-style AUV could.

What does a typical mission look like?

Sentry's unique control scheme means that propelling itself to the bottom like torpedo-shaped AUVs typically do by swimming in a circle would burn up a lot of battery power. Since mission length is primarily limited by the batteries, that's no good. It would also be slow. Instead, we launch Sentry with “descent weights" that make it negatively buoyant, so it descends at ~0.6m/s. Once it detects the sea floor with one of its sonars, it drops the descent weights3 and becomes neutrally buoyant. It then spends 8-20+ hours swimming pre-programmed survey lines. At the end of the dive, it drops the ascent weights and floats to the surface at ~1m/s. This is the same speed as a leisurely stroll -- ascent and descent can each take well over an hour in deeper water.

Wait. Isn't Sentry autonomous? Why do humans need to monitor it?

Even if a dive goes perfectly, we will have human interaction twice: first to correct the robot's position estimate and once to tell it to drop the ascent weights.

Initial Shift

When Sentry is at the surface, it knows where it is using GPS. However, this information isn’t used in the control loop — we just tell it where the start of the survey is, and it assumes that it has been dropped exactly there.

Once within ~100m of the ocean floor, Sentry’s DVL4 is able to make observations of Sentry’s relative velocity. Combined with pressure/depth data and INS accelerations / orientation, a simple kalman filter can estimate Sentry’s position relative to wherever the dive started.

However, when Sentry is in the middle of the water column, there aren’t any good sensor inputs for it to estimate its position: double-integrating accelerations is noisy and diverges quickly. So, its onboard code just assumes that it doesn’t drift at all. (Hah.)

Whenever it gets to the bottom, the operator can compute how much it drifted by using the ship’s USBL to get Sentry’s position relative to the ship and comparing that to where Sentry thinks it is.

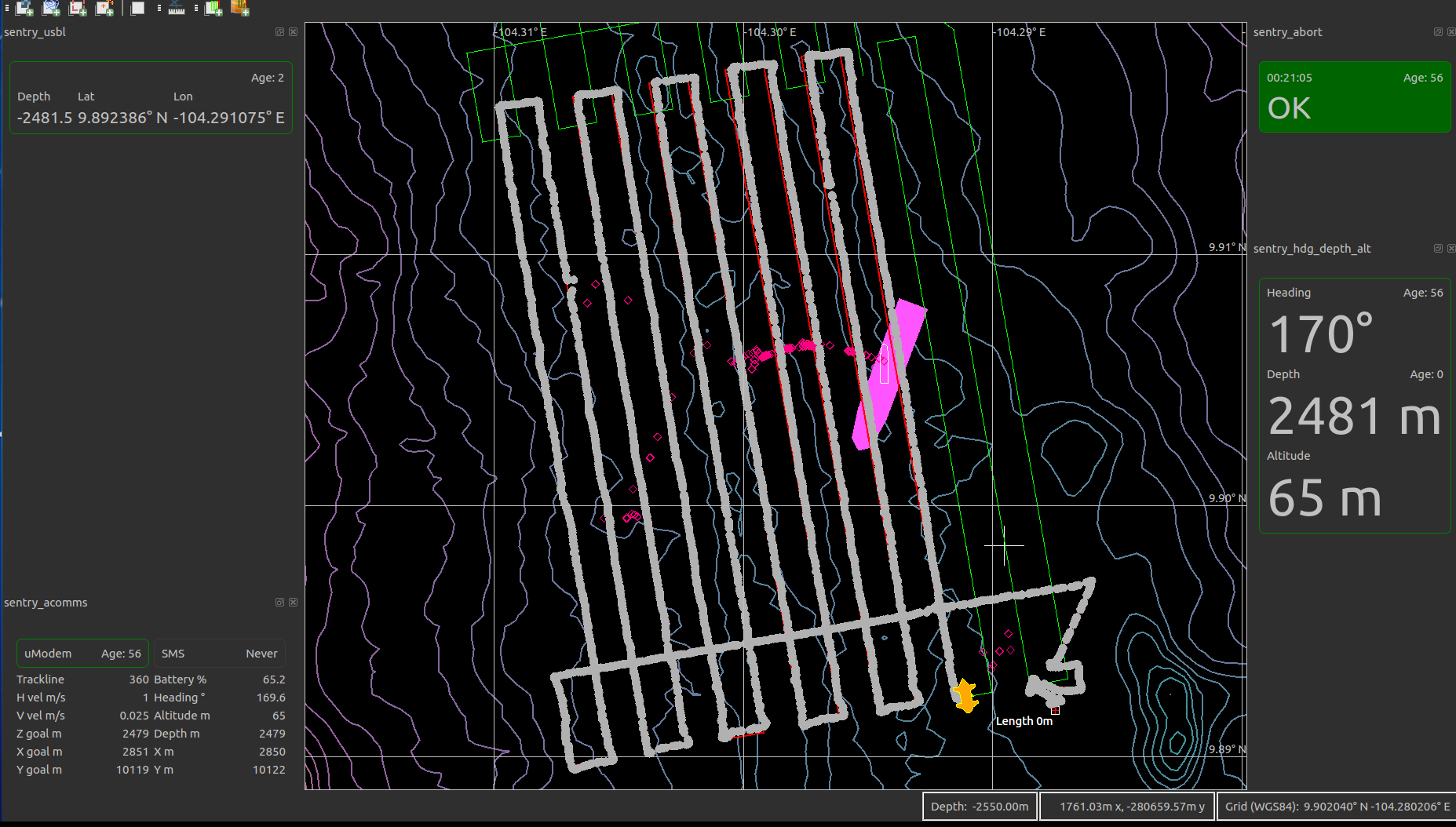

“navg3” interface, displaying the local bathymetry (contour lines) the ship’s current position (magenta polygon), Sentry’s position (yellow robot), the commanded path (red/green lines), and where Sentry has actually traveled (grey dots)

The surveys are designed with a few ninety degree turns at the start, since observing a corner in sentry’s path makes it easy to compute the offset. That offset is then manually entered and acoustically transmitted to sentry, allowing us to follow tracklines to ~10m accuracy, rather than swimming the pre-planned survey offset by up to hundreds of meters.

Yes, it is theoretically possible to send the USBL fixes down and have Sentry update its own shift. This is definitely on the wishlist, but we have limited developer time and money. However, it's also more complicated than you might think. The USBL fix jumps around, which means that the resulting position estimate can jump. (This is also a common problem for autonomous ground vehicles, where the GPS positions jump but you want control to be smooth and relative to what the sensors see.) Overcorrecting to a jumpy position estimate isn't good for a survey, where it is more important to swim a grid pattern with evenly spaced coverage than it is for the lines to be exactly at a given coordinate. We also sometimes re-purpose the shift to move Sentry out of the way of other assets that are in the water.5

Terminating the dive

Missions are typically designed with a holding pattern at the end, and if everything has gone well, the operator will manually trigger the ascent when the ship is in position and ready to recover the AUV. We don't want Sentry to just pop up to the surface whenever the primary survey is finished -- it's safer at the sea floor! Once on the surface, Sentry is subject to currents, waves (wear-and tear on mechanical parts) and could get run over by another ship. Plus, all of our acoustic communications stop working when Sentry is bobbing at the surface with the transducers out of the water. At that point, we are limited to receiving text messages with its GPS coordinates via Iridium, a radio beacon that the ship can detect to get a bearing, visual strobes, and a short-range freewave radio (useful within a few hundred meters to joystick Sentry into position for recovery).

Sentry would cost millions to replace and there's only one. We really want it to come back from every mission. So, we have a variety of ways for Sentry to decide to drop its weights and return to the surface:

- The operator uses the acoustic modem to send a message that is processed through the software stack, causing the cams to open and drop the weights. This is the preferred method.

- The operator uses a separate transducer to send an acoustic command to the XRs/LBL transponders. On the vehicle, they are entirely self contained, running on internal battery power, and have direct control over both the cams and the burnwires.6 The transponders themselves are also redundant -- there are two of them (one listens at 14kHz and the other at 10.5kHz), and each controls the motor to one ascent weight and the burnwire to the other. So, if one fails (or the acoustic conditions aren't favorable for its frequency) the other is sufficient to drop both weights.

-

Something goes wrong in the mission, triggering an abort in software:

a. If battery percentage goes below 9% the weights will be released. Some battery power is kept in reserve for the ascent and for driving on the surface so we can remote control it into position to be snagged by the ship.

b. Similarly, if a critical process dies, the vehicle will abort.

c. If Sentry completes its mission and runs out of track lines, it aborts. This means that missions are always designed to have a holding pattern at the end, giving us a buffer of when to start the recovery.

-

The abort timer runs out. Even if the entire computing stack has died, preventing the above methods from working, the XRs have a countdown after which they will release the weights.

Logistics / Coordination

Sentry’s watchstander is also the point person for any ship operations that could affect Sentry. This type of thing will have been negotiated beforehand with the expedition leader, but the EL won’t always be awake at the time, and somebody has to be awake to answer questions about whether ship activities will cause an issue for Sentry.

Our main priorities are to not have Sentry run into anything else (we’re generally OK with ~200m horizontal separation, or 100m vertical) and to ensure that we have good enough tracking with the ship’s USBL to “renavigate” the dive data to precisely localize it. These interactions might include:

-

When performing joint operations with multiple assets in the water, we might use a shift command to avoid Jason’s work site, if the surveys are close together. (Jason is a tethered ROV that is often also operated off the Atlantis)

-

On one dive, the scientists wanted to do a CTD cast right in the middle of our survey area, which had to be timed precisely to avoid a potential collision. This was actually really cool — they used chemical data from Sentry's previous dive to precisely target the plume from a subsea vent, while Sentry was performing a lower-altitude camera survey in the same area.

-

Dumping slops buckets. Kitchen scraps have to be dumped far away from Alvin’s dive site to avoid attracting sharks. The bridge will coordinate with us to minimize the impact on our USBL tracking while still transiting far enough away to dump them.

-

In order to maximize science accomplished per ship hour, the chief scientist may want to move Atlantis outside of range of Sentry comms.

Failure handling

Having humans in the loop results in a more robust system than you could have if all failure handling was required to be autonomous. It would be more satisfying from a robotics point of view if it could handle all failures on its own, but we only have one robot, and it has only done 550 dives (which is a lot for a platform like this!) so we're still discovering new failure modes. And detecting them all is a much harder problem. So, here are some examples of human interventions:

- On one dive, a corrupted bit in a sensor reading caused Sentry’s position estimate to go unstable, which led to Sentry running away. The watchstander was able to recognize this and intervene.

- On another dive, we could see that Sentry was struggling to maintain the programmed altitude with a forward speed of 1 m/s, so we lowered the commanded speed (thus switching it to a different control scheme), after which it was able to follow the planned tracks. it only finished part of the mission thanks to the reduced speed, but that's better than none, and far better than waking up the ship's crew to recover Sentry in the middle of the night. When we recovered Sentry, we discovered that one of the fin servos had failed, which was causing the control issues.

- Our bottom-detection algorithm for deciding when to drop weights at the start of a dive is very very simple, and sometimes triggers due to noisy DVL data (this has been happening a lot this cruise.) However, it is definitely better to drop the descent weight too early than to plow into the bottom at 1 meter per second. After dropping weights, Sentry will transition into a bottom-following mode, but that mode struggles when it doesn’t have good altitude data, because it can’t always figure out whether the sensor is failing to provide data because its too close to the ground or too far away. On a descent, the operator knows that the robot needs to dive deeper, so we can send an override command telling the bottom follower to drive down.

Cool! But how did you know that there was a problem in the first place? How can you communicate with something that's under up to 6km of water?

Acoustics!

Underwater, you're pretty much limited to sound waves. Under perfect conditions, you might get a few hundred meters with visible light. GPS and Radio frequencies are much worse -- the conductivity of sea water mean that they attenuate within meters. So, we have a number of different acoustic instruments used for tracking and talking with Sentry.

USBL

The ultra short baseline (USBL) system is a commercial product that is permanently installed on Atlantis. A pole is deployed sticking through the hull (to get the transducers farther from any noise on the ship), and limits our speed to ~3 knots. Any assets that go in the water have a beacon attached, and the big head is able to get bearing and range to those beacons.

The Ranger2 GUI that is used for interacting with Atlantis's USBL. The ship’s position is at the center of the concentric circles, while Sentry’s beacon is marked with a green cross. The fading trail of green dots shows Sentry's past positions.

This system is used for tracking Sentry; Atlantis has a display in the bridge, and the mate on watch will use it to stay close. We also use the positions reported by the USBL to post-process Sentry’s navigation estimates. This provides a big improvement in how well we can localize the scientific data -- there’s no GPS underwater, and dead-reckoning drifts over time.

SMS

The Avtrak USBL system also includes the ability to send short “SMS” message to the vehicle. We are limited to 64 ascii characters, and there is some awkward buffering at either end.

Whifflenav

I have no idea where this whimsical name came from. It’s a legacy set of hardware that used to be used in long base line navigation: they would put beacons on the sea floor, and a robot could estimate its location by calculating ranges to multiple beacons. Now we have two independent beacons on the robot and they’re used to obtain the two-way travel time between the ship and the robot.

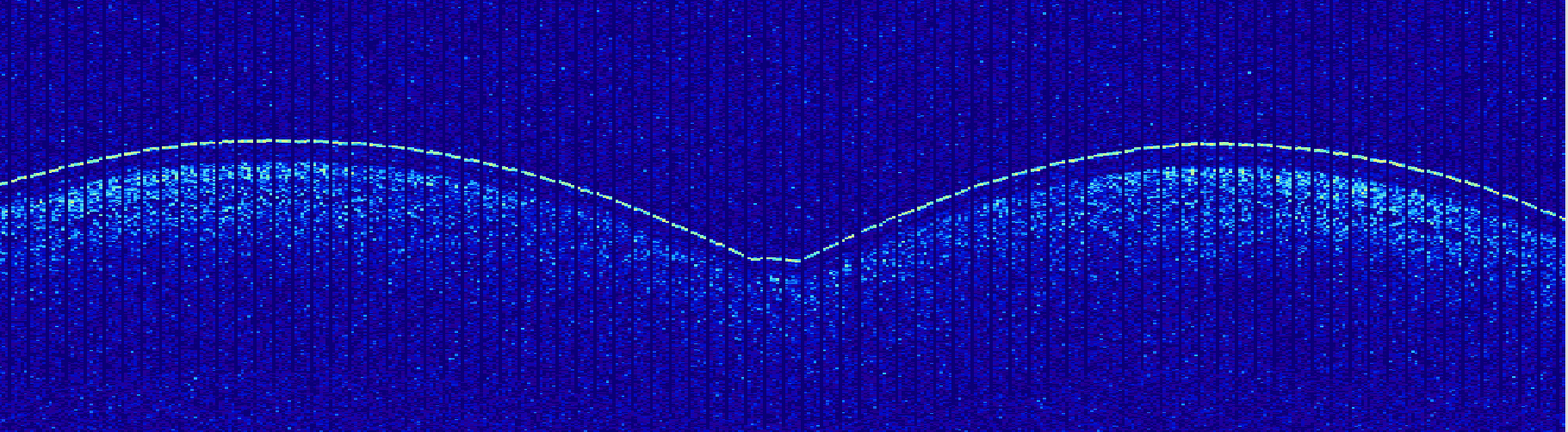

Plot showing intensities from the whifflenav transducer at 13kHz. Horizontal axis is time, and vertical is effectively range (it’s also time-since-ping, which becomes range after adjusting for the speed of sound in water). In this image, Sentry has been swimming back and forth -- you can see the turns when the line’s slope changes. In this region the ocean floor is very hard and rough, so in addition to the direct return from Sentry's beacon there are multipath effects (energy that traveled Sentry -> ocean floor -> Atlantis) that show up as a trail of reflections beneath/after Sentry’s sharp return.

The Whifflenav has the longest range of any of our acoustic instruments, and on dives where Sentry travels far from the ship, watchstanding can devolve into making sure that the observed ranges have inflection points corresponding to turns in the dive plan.

The XRs are NOT used for communicating with the robot; historically, they were used to send a few bytes of information, but now, the only command they respond to is to abort the mission.

Micromodem

The Micromodem provides our highest bandwidth acoustic communications with Sentry. It has a shorter maximum range than the XRs, but this cruise, we’ve been getting micromodem messages from Sentry at ranges up to 9.5 km!

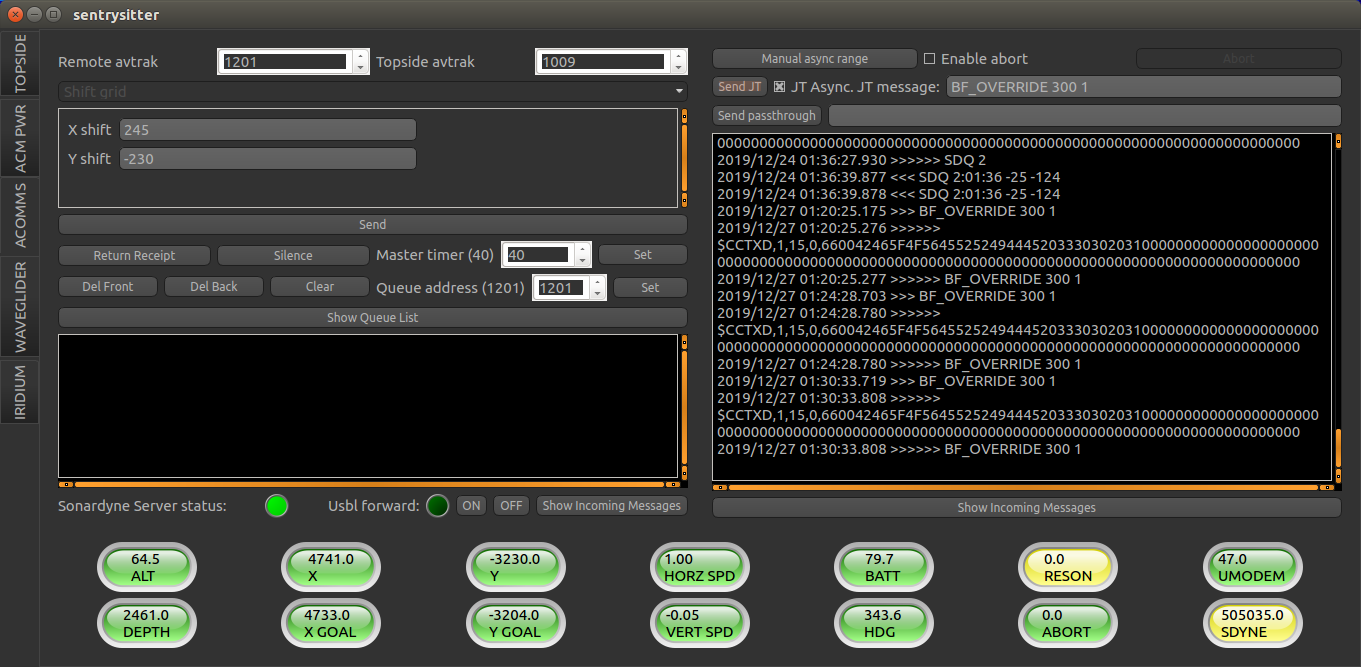

Every minute on the minute, Sentry will send an update with basic information including its depth, altitude, heading, speed, and where it thinks it is. In addition, we have a number of “queues” that we can request, which have been hand-tuned to pack relevant information into a 64 byte message. For example, if sentry’s reported altitudes suggest control issues, we can request the status of its actuators. Or, at the start of a big camera survey, we might double-check that the frame count is incrementing to verify that the camera turned on and is working.

Sentrysitter GUI. The radio buttons at the bottom are populated by the acoustic messages from Sentry, and the controls at the top are for transmitting additional commands.

The micromodem hardware is capable of sending significantly more information than this — at maximum data rates, it can encode ~2048 bytes in a ~15 second long transmission. My major project at the moment is developing the software support to make better use of all that unused bandwidth.

Watchstanding is a great time to catch up on media consumption!

- Actually, I'm salaried, so regardless of your opinions about having developers be intimately familiar with the systems they work on, it's cheaper to send me to sea than a tech who would get overtime. I'm not complaining! ↩

- Huge thanks to the Chief Scientist Eric Cordes and his team for not putting an embargo on this data, so I could post it publicly within 2 years of the cruise. ↩

- Yes, they are left on the ocean floor, which can require permits. We try not to drop them in the middle of the survey area, if it's somewhere with interesting hydrothermal vents. ↩

- Doppler Velocity Logger — this instrument has 4 sonar beams angled out, and by using the doppler shift of each beam and assuming that whatever surface is generating a return is also stationary, you can compute the 3D velocity of the robot. This is similar to how "radar guns" are able to detect speeding vehicles. ↩

- We don't have a good way to send updated plans to Sentry during a dive; however, updating the offset allows us to arbitrarily translate the existing survey geometry. ↩

- The primary release is a cam that turns to release the weight and the second is a burnwire, which corrodes within ~30 minutes when current is run through it. ↩